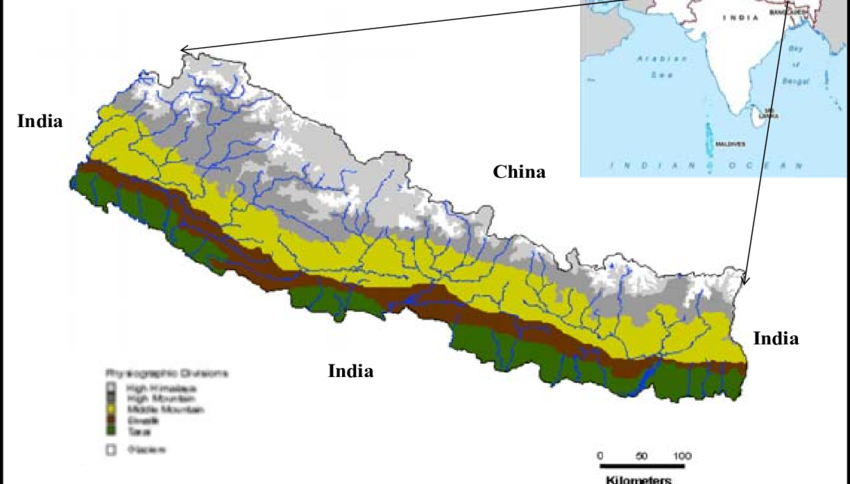

The history of Awadh is often told from the perspective of its grand cities Ayodhya, Faizabad, Lucknow. But rarely do we explore its northern edge, where the plains meet the hills. Here lies a fascinating and underexplored story: the tale of Silliana, an ancient frontier between the fertile lands of Kosala and the rising Siwalik hills of present-day Nepal. This transitional zone not only shaped the ancient geography of the region but also laid the cultural foundations for the Awadhi presence in Nepal today.

1. Silliana: The Ancient Hill–Plains Gateway

In ancient geography, Silliana (sometimes spelled Saliana or Sulliana) referred to the lower hill region immediately north of Uttara Kosala, with the fertile Terai plains stretching out before it.

Kosala, the kingdom of the legendary Lord Rama, was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas (great realms) of early India. Uttara Kosala formed its northern expanse, brushing against what is now southern Nepal.

Silliana’s significance was twofold:

- Strategic location – It acted as a natural gateway between the plains and the hills, enabling trade, migration, and cultural exchange.

- Cultural fusion – The region absorbed the language, religion, and customs of Kosala while adapting to the rhythms of the Himalayan foothills.

- Though Silliana itself was not a formal kingdom, its inclusion in ancient territorial descriptions shows it was a recognized cultural–geographic entity.

2. From Kosala to Awadh: Continuity Across Centuries

As centuries passed, the ancient Kosala region evolved into Awadh (Oudh), a politically powerful and culturally rich province. By the medieval period, Awadh was a jewel of the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire, famous for its refined etiquette, courtly arts, and cuisine.

Awadh’s influence naturally flowed northward into the Terai belt:

- Merchants carried goods—textiles, spices, and handicrafts—across the border.

- Farmers and artisans migrated seasonally between the plains and foothills.

- Pilgrims traveled between holy sites in Nepal and Awadh, strengthening religious and cultural bonds.

- This exchange mirrored the ancient function of Silliana as a link between two landscapes.

3. The 18th–19th Century: Politics and Borderlands

The rise of the Gorkha Kingdom in the mid-18th century reshaped the political map. Under King Prithvi Narayan Shah and his successors, Nepal expanded into the Terai, incorporating many Awadhi-speaking areas.

However, the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–1816) brought dramatic changes. The Sugauli Treaty forced Nepal to cede large parts of the Terai to the British East India Company, only for some of these lands to be returned shortly after as a goodwill gesture.

Meanwhile, Awadh itself faced British encroachment. In 1801, parts of its territory were ceded to the British, and by 1856, the entire kingdom was annexed. This created a colonial border that split communities but did not sever cultural ties.

4. Awadhi in Nepal Today: A Living Heritage

While “Silliana” has vanished from administrative maps, its spirit survives in the Terai districts of Kapilvastu, Rupandehi, Nawalparasi, Banke, Bardiya, and Kanchanpur—regions where Awadhi is still widely spoken.

Key elements of this living heritage include:

- Language – Awadhi remains a vibrant mother tongue for thousands, contributing to Nepal’s rich linguistic diversity.

- Cuisine – Kachori, litti, malpua, and handi-style cooking are culinary treasures passed down through generations.

- Festivals – Holi, Chhath, and Ram Navami are celebrated with the same fervor as in the plains of Uttar Pradesh.

- Oral traditions – Folk tales often blend the histories of Kosala, Awadh, and local Nepalese lore, keeping the shared past alive.

5. Why Silliana Matters in Modern History

Understanding Silliana’s place in history does more than satisfy curiosity—it bridges the gap between mythic geography and modern cultural identity. It shows how:

- Ancient geographic zones influenced present-day settlement patterns.

- Cultural flows often survive political changes and colonial boundaries.

- Nepal’s Terai is not just a peripheral strip of land, but a historical meeting ground for civilizations.

- From the foothills of ancient Silliana to the vibrant markets of today’s Terai towns, the story of Awadh and Nepal is one of continuity, adaptation, and shared heritage.

Conclusion

The journey from Silliana to modern Awadhi Nepal is a reminder that history is not confined to borders drawn on maps. The same pathways that carried Kosala’s pilgrims, Awadh’s merchants, and Mughal-era traders now carry festival processions, wedding parties, and cultural exchange across the plains and hills. In every Awadhi phrase spoken in Nepal, in every shared festival, and in every recipe passed down through generations, Silliana still whispers its story.